About the department: I am a lecturer (assistant professor) in evolutionary paleobiology in the Department of Earth Sciences at Cambridge. Because my research is specimen-based and focuses on vertebrate evolution, I maintain strong links with several other institutions within the university, such as the Department of Zoology, University Museum of Zoology, and the Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences. One unusual aspect of my job at Cambridge is that the university is made up of 31 autonomous colleges, so in addition to my ‘normal’ departmental job of research and lecturing, I am also a fellow of Christ’s College, where I teach small group supervisions. Christ’s College is an exciting multi-disciplinary community, and also happens to be where Charles Darwin studied as an undergraduate.

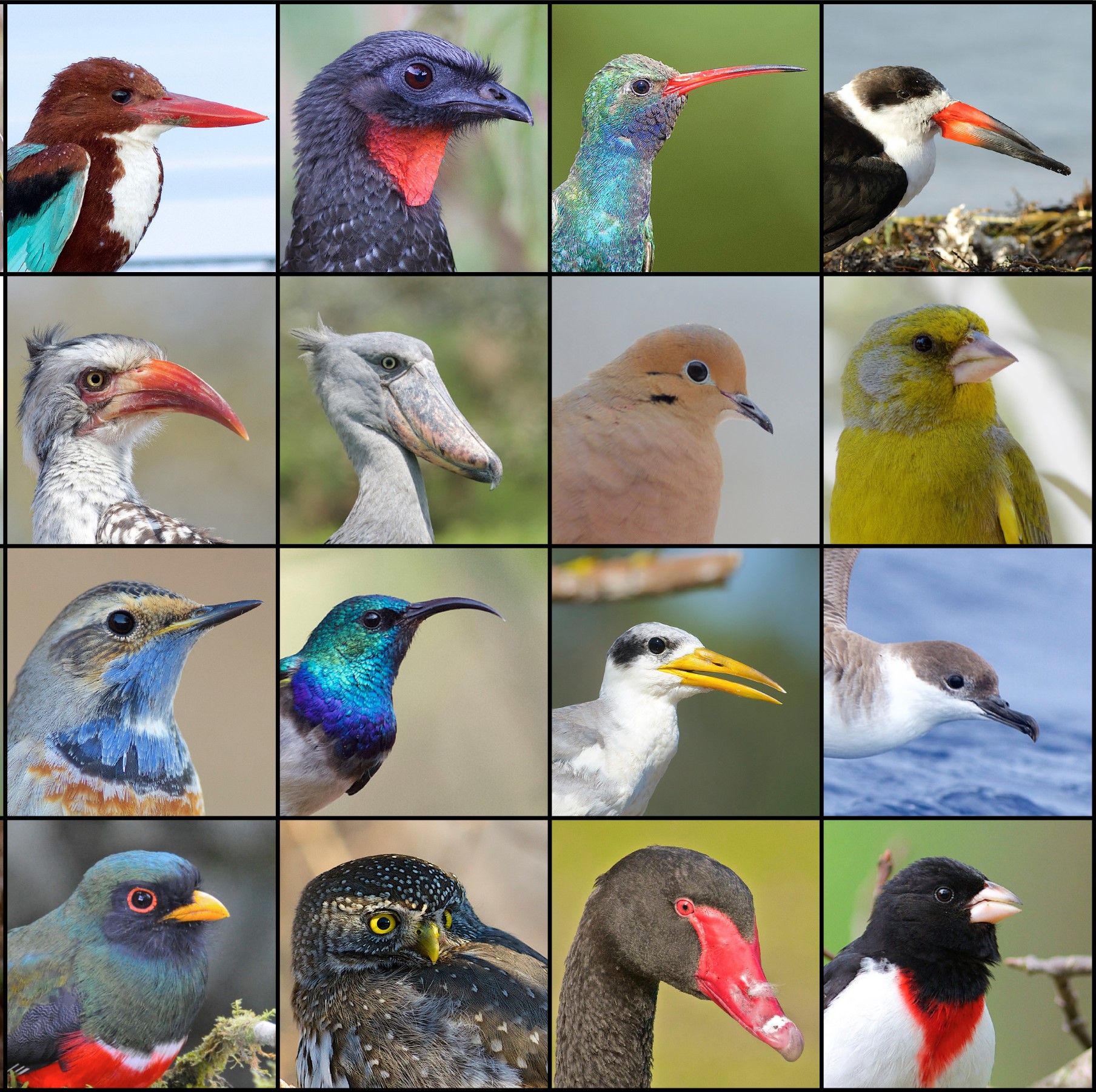

About the research: My research is mostly focused on the macroevolutionary history of birds. I am interested in how the distinctive characteristics of birds arose among Mesozoic dinosaurs (e.g., feathers, warm-bloodedness, toothless beak), as well as how, when, and where modern avian biodiversity originated. I also occasionally address similar questions in other groups of vertebrates, and have worked on sharks, snakes, turtles, non-avian dinosaurs, and whales.

How do you approach mentoring new lab members? Vertebrate paleontology is an exciting subdiscipline of evolutionary biology, but the perceived rarity of key specimens and a challenging job market can sometimes lead to an unwelcoming environment for young researchers. The most important lesson for students joining my research group is to be kind and stay positive, even in the face of challenges such as these. Unraveling mysteries from the fossil record is a privilege, and if you stay excited about your science and maintain a positive attitude, things will work out well!

When was your first Evolution meeting, and how did it affect your career? My first Evolution meeting was in Raleigh in 2014, and it changed my career forever. Before then I had mostly limited myself to paleontology conferences, so attending Evolution allowed me to meet many amazing comparative biologists and evolutionary ornithologists for the first time. These included legends like Scott Edwards, but also many brilliant young researchers who are all rising stars and wonderful people (Deren Eaton, Shane DuBay, Jessica Oswald, Ryan Terrill, Caroline Judy, and Ben Winger, to name a few). At that meeting I received the W.D. Hamilton Award for my talk on the evolution of the avian shoulder joint, which was a massive confidence boost midway through my PhD. It was really validating to learn that SSE clearly valued paleontology and appreciated its relevance to evolutionary biology, and humbling to compete for the prize alongside many great researchers representing a huge breadth of research subjects.

Besides research, how do you promote science? Paleontology lends itself really well to public outreach (it’s often said that fossils are the lens through which many children first experience the thrill of science). With that in mind, I have prioritized participating in public engagement opportunities throughout my career, ranging from museum tours, public talks, school visits, media outreach, and occasionally writing articles for public audiences. I love talking to people about the evolution of birds and the fossil record, and think these efforts can help improve science literacy in the general public on subjects beyond paleontology and evolution.

What book should every evolutionary biologist read? I read some inspiring books on evolutionary biology and the fossil record as an undergraduate, including Neil Shubin’s

Your Inner Fish and Sean Carroll’s

Endless Forms Most Beautiful. Thinking back, the book that influenced me the most at that point was probably

Dry Store Room No. 1 by Richard Fortey, which describes the early stages of his career as a paleontology curator at one of the world’s great museums, the Natural History Museum in London. Fortey conveys such awe and excitement about uncovering forgotten wonders within the Natural History Museum’s collections, and anyone who has had the privilege of doing collections-based research will understand the emotions he describes. I feel extremely lucky to get to follow in Fortey’s footsteps and frequently work within natural history museums myself, and think anyone curious about specimen-based research should definitely give

Dry Store Room a read.

What do you enjoy doing in your spare time? I am a keen birder and

wildlife photographer, and love tracking down new species in exciting corners of the world. I also love playing sports, and have recently joined basketball and ice hockey teams at Cambridge (that’s not always possible in the UK, and is very welcome for a Canadian expat like me!).

Daniel J. Field

Daniel J. Field